Surprise packages sent by cancer cells can turn normal cells cancerous, but Cornell scientists have found a way to keep their cargo from ever leaving port. Published in Oncogene in January 2012, their study demonstrates the parcels’ cancer-causing powers, describes how they are made, and reveals a way to jam production. Treatments that follow suit could slow tumor growth and metastasis, the spread of cancer to new parts of the body.

Remote recruiting through inter-cellular mail lets cancer cells grow their ranks without having to move. While most cells communicate through a standard postal system of growth factors and hormones, cancer cells and stem cells use bulkier parcels called microvesicles. These big packages are stuffed with unconventional cargo that boosts the survival and growth rates of recipient cells and can dramatically alter their behavior and surrounding environment. The cargo of microvesicles includes unique sets of proteins that often reflect their cell of origin and are capable of completely changing a cell’s form and function.

“Stem cells make microvesicles containing one set of proteins that can help heal damaged tissue, while cancer cells make malignant microvesicles called oncosomes that contain another set of proteins which facilitate the growth and spread of tumors,” said Dr. Richard Cerione, professor at the College of Veterinary Medicine and co-author.

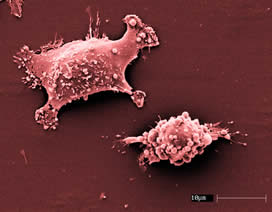

Dr. Marc Antonyak and graduate student Bo Li, co-authors and researchers in Cerione’s lab, examined cells in culture to observe the effects of oncosomes on normal cells. They focused on fibroblasts, a normal cell type that is often found associated with human tumors and helps to facilitate tumor growth.

“We incubated healthy fibroblasts together with aggressive breast cancer cells,” said Antonyak. “Although we’d disabled the cancer cells from forming tumors on their own, they kept pumping out oncosomes. The fibroblasts that were bathed in these oncosomes began turning cancer-like, living longer, growing faster, and forming tumors.”

Using a variety of techniques to parse out participating proteins, including immunoblot analysis, immunofluorecence, and electron microscopy imaging, Antonyak identified each link in this pathway and traced it back to the first: a protein called RhoA that acts like a lever initiating microvesicle production. Cancer cells crank production into overdrive, said Antonyak, but jamming the lever could stop the whole assembly line.

“Even if we immobilize cancer cells, as long as they can make these microvesicles they can continue spreading vital components for the development of cancer,” said Cerione. “It’s clear that microvesicles can change the behavior of cells and play an important part in cancer progression. Treatments targeting the microvesicle production pathway we’ve outlined could have a real impact on slowing cancer progression.”

—–

http://vet.cornell.edu/news/CancerCargo.cfm